Lectionary Passage: John 3: 14-21 (Lent 4B)

14And just as Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, so must the Son of Man be lifted up, 15that whoever believes in him may have eternal life. 16“For God so loved the world that he gave his only Son, so that everyone who believes in him may not perish but may have eternal life. 17“Indeed, God did not send the Son into the world to condemn the world, but in order that the world might be saved through him. 18Those who believe in him are not condemned; but those who do not believe are condemned already, because they have not believed in the name of the only Son of God. 19And this is the judgment, that the light has come into the world, and people loved darkness rather than light because their deeds were evil. 20For all who do evil hate the light and do not come to the light, so that their deeds may not be exposed. 21But those who do what is true come to the light, so that it may be clearly seen that their deeds have been done in God.”

This is it: THE verse. So what we do with THE verse? It’s on street corners and billboards and T-Shirts and tattoos and faces and signs at sporting events. I think it is often read as some sort of great reward for doing the right things. You know, if you do everything you’re supposed to do, you’ll be rewarded when it’s all said and done. And if you don’t, well you’re just out of luck. So, look at me…do what I do, go to church where I go, be what I am, look like I look. I’m saved; are you? (Define that! Do we really understand what that means?)

But I think we’ve read it wrong. For God so loved the world—not the ones in the right church or the right country or the right side of the line—but the WORLD. God loved the world, everything about the world, everyone in the world, so much, so very, very, VERY much, that God came and walked among us, sending One who was the Godself in every way, to lead us home, to actually BRING us home, to lead us to God. Are you saved? Yes…every day, every hour, over and over and over and over again. I’m being saved with every step and move and breath I take. I think that’s what God does. God loves us SO much that that is what God does. God is saving us. God came into the world to save the world. So why would we interpret this to mean that God somehow has quit loving some of us or that we have to somehow bargain with God to begin loving us or that “being saved” is a badge of honor? See, God loves us so much that God is saving us from ourselves.

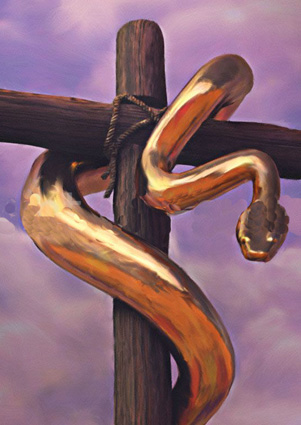

The reference to the snake refers to the Old Testament lectionary reading for this week (Numbers 21:4-9 if you need to be reminded of it) It is the account of the Lord sending poisonous serpents into the wilderness that can be countered by making a serpent and putting it on a pole so that everyone who looks at it will live even though they were bit by a poisonous snake. (OK….whatever!) So, essentially, it’s like this: You think your main problem is snakes? Alright, here it is. Look at it hanging there on the tree. Quash your fear, let your preconceptions go. There…no more snakes. You don’t have to fear snakes.

So, this time? You have let the world order run your life. You have become someone that you are not. You have allowed yourself to be driven by fear and preconceptions and greed. You have opted for security over freedom, held on to what is not yours, and settled for vengeance rather than compassion and love. I created you for more than this. I love you too much for this to go on. Look up. Look there, hanging on the tree, there on the cross. Stare at the Cross. Enter the Cross. See how much I love you. In this moment, I take all your sin, all your misgivings, all your inhumanity and let it die with me. All is well. All is well with your soul. There…no more death. You don’t have to fear death.

In this season of Lent, we inch closer and closer to the cross. We shy away. It’s hard to look at. But perhaps it’s not the gory details, but the realization that we are the culprits. Lent provides a mirror into which we look and find ourselves standing in the wilderness of ourselves, sometimes fearful of what we might find. But the Cross is our way out (not our way “in” to God, but our way “out” of ourselves). Because God loves us so much that God cannot fathom leaving us behind. The Cross is the place where we finally know that. For God so loved the world that he gave his only Son, so that everyone who believes in him may not perish but may have eternal life. Indeed, God did not send the Son into the world to condemn the world, but in order that the world might be saved through him.

Thomas Long, the well-known professor of preaching at Candler School of Theology once said it like this: In Christian language, to be truly human is to shape our lives into an offering to God. But we are lost children who have wandered away from home, forgotten what a truly human life might be. When Jesus, our older brother, presented himself in the sanctuary of God, his humanity fully intact, he did not cower as though he were in a place of “blazing fire and darkness and gloom.” Instead, he called out, “I’m home, and I have the children with me.”

In this wilderness season, it is easy to feel lost. It is easy to feel alone. It is easy to wonder where to turn next. But this passage is a reminder that we are not alone. God is always there and has given us a promise. You…you are my beloved child. Believe. Belove. Know that I am always with you, always carrying you home.

Salvation is not only a goal for the afterlife; it is a reality of everyday that we can taste here and now. (Henri J.M. Nouwen)

Grace and Peace,

Shelli