|

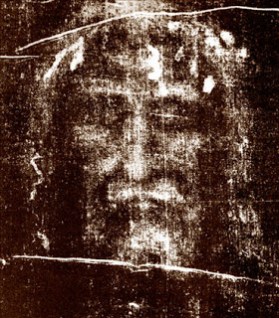

| The Shroud of Turin |

Lectionary Passage From Today: John 12: 20-21 (22-36)

Now among those who went up to worship at the festival were some Greeks. They came to Philip, who was from Bethsaida in Galilee, and said to him, “Sir, we wish to see Jesus.”

“Sir, we wish to see Jesus.” Hmm! I supposed you and everyone else! We ALL wish to see Jesus. But somehow that often eludes us. Oh, we know that Jesus existed. We have the stories and all. But what does it mean to see Jesus, REALLY see Jesus? It’s got to mean seeing more thatn Jesus as a prophet, or a mighty king or a high priest. It’s got to mean more than standing alongside Jesus the teacher, Jesus the healer, or even Jesus the friend (Although I would be careful with that one–careful that we do not somehow pull the very human Jesus down to our level. Jesus was FULLY human. Jesus was what we’re called to be.) No, seeing Jesus means beoming a part of The Way that is Christ, entering the mystery, the awe, the very essence that is God. It means being lifted up and gathered in.

So, when these Greeks came asking to see Jesus, what were they seeking? Do you think they wanted someone to lead them? Probably not…they had their own leaders. They had their own teachers. They had their own friends. What they desired was what we all desire–for it all to mean something. They wanted to understand. They wanted some sort of proof. They wanted to see Jesus.

There is a story that is told in Feasting on the Word (Year C, Volume 2) of Anthony the Great, the fourth-century leader of Egyptian monasticism: A Wise older monk and a young novice would journey each year into the desert to seek the wisdom of Anthony. Upon finding him, the monk would seek instruction on the life of prayer, devotion to Jesus, and his understanding of the Scriptures. While the monk was asking all the questions the novice would simply stand quietly and take it all in. The next year the well-worn monk and the young novice again went into the desert to find Anthony and seek his counsel. Again the monk was full of questions, while the novice simply stood by withouot saying a word. This pattern was repeated year after year. Finally, Anthony said to the young novice, “Why do you come here? You come here year after year, yet you never ask any questions, you never desire my counsel, and you never seek my wisdom. Why do you come? Can you not speak?” The young novice spoke for the first time in the presence of the great saint. “It is enough just to see you. It is enough for me just to see you.”

We all wish to see Jesus. But seeing Jesus is not about seeing with our eyes. It is not about information-collecting. It is not about understanding. It is not about proof. It is, rather abut Presence. The vision is that all would see Jesus and finally have their thirst quenched by the Divine. But you have to realize for what it is you thirst. We thirst for the Divine; We thirst to see Jesus. The Cross is the instrument through which we see Jesus. It is ont the Cross that Jesus becomes transparent, fully revealed. Seeing Jesus means that we see that vision of the world that God holds for us. And seeing Jesus also means that we see this world with all of its beauty and all of its horror. We see the way that God sees. And we finally see who we are. And, finally, we are whole. Seeing Jesus makes us whole and being whole means that we can finally see Jesus and we see everything else that way that it was meant to be.

In The Naked Now: Learning to See as the Mystics See, Fr. Richard Rohr talks of the experiences of three ment who stoop by the ocean, looking at the same sunset. As he relays, one man saw the immense physical beauty and enjoyed the event itself. This man…deals with what he can see, feel, touch, move, and fix. This was enough reality for him…A second man saw the sunset. He enjoyed all the beauty that the first man did. Like all lovers of coherent though, technology, and science, he also enjoyed his power to make sense of the universe and explain what he discovered. He thought about the cyclical rotations of planets and stars. Through imagination, intuition, and reason,, he saw…even [more]. The third man saw the sunset, knowing and enjoying all that the first and the second men did. But in his ability to profess from seeing to explaing to “tasting,” he also remained in awe before an underlying mystery, coherence, and spaciousness that connected him with everything else. He [saw] the full goal of all seeing and all knowing. This was the best. It was seeing with full understanding.

In order to see Jesus, you have to lay yourself aside and breathe in the mystery of it all. You have to open yourself to being recreated with the eyes of the Divine.

On this fifth Sunday of Lent, close your eyes and breathe in the mystery that surrounds you. Close your eyes and feel the Presence of Christ that pervades your life. Close your eyes that you might see.

Grace and Peace,

Shelli